WHAT IF All Humans Had Alzheimer’s?

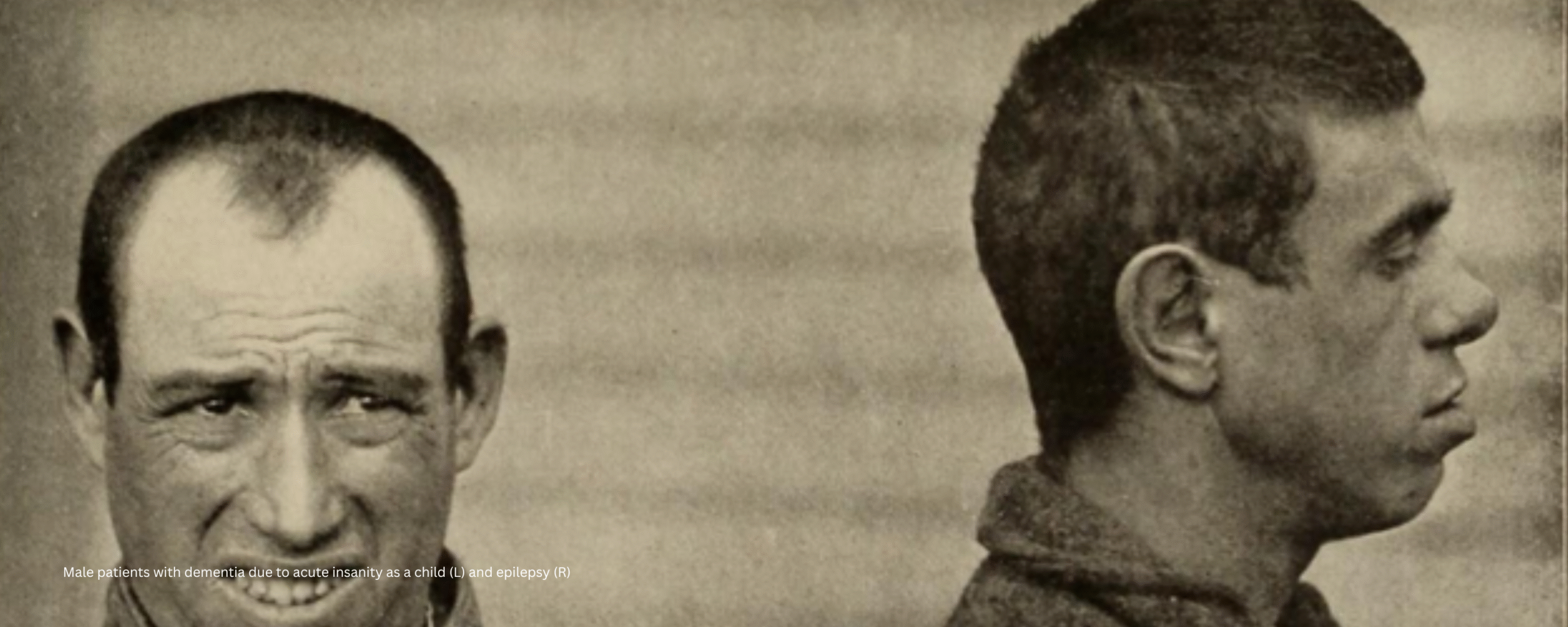

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterised by the build-up of beta-amyloid plaques and tau tangles in the brain, leading to synaptic dysfunction and eventual neuronal death. The condition typically manifests as short-term memory loss, language impairment, and disorientation, progressing to global cognitive decline.

If every human being were affected by Alzheimer’s from birth, the first and most obvious outcome would be the near-complete erasure of the capacity for long-term episodic memory — the ability to remember specific events and experiences. Procedural memory (skills and habits) might remain intact longer, but the narrative memory that allows societies to record history, pass on knowledge, and plan for the future would be effectively absent.

Memory is the foundation of civilisation. Remove it, and the structure collapses.

The “What If” Series: Exploring Alternate Realities

History, science, and philosophy are built on facts — but sometimes, the most powerful truths emerge from imagination. The “What If” series dives into alternate realities, where one shift in medicine, society, or human nature rewrites everything we know. From worlds without penicillin to societies without nights, these thought experiments challenge our assumptions, blur the line between possibility and impossibility, and force us to confront the fragile balance that shapes human existence.

Impact on History and Knowledge Transmission

Human civilisation relies on a shared historical narrative. Oral traditions, written archives, and digital databases are our tools for overcoming the limitations of individual memory. In a population where no one can reliably store new long-term memories, these systems would be meaningless without the ability to interpret them.

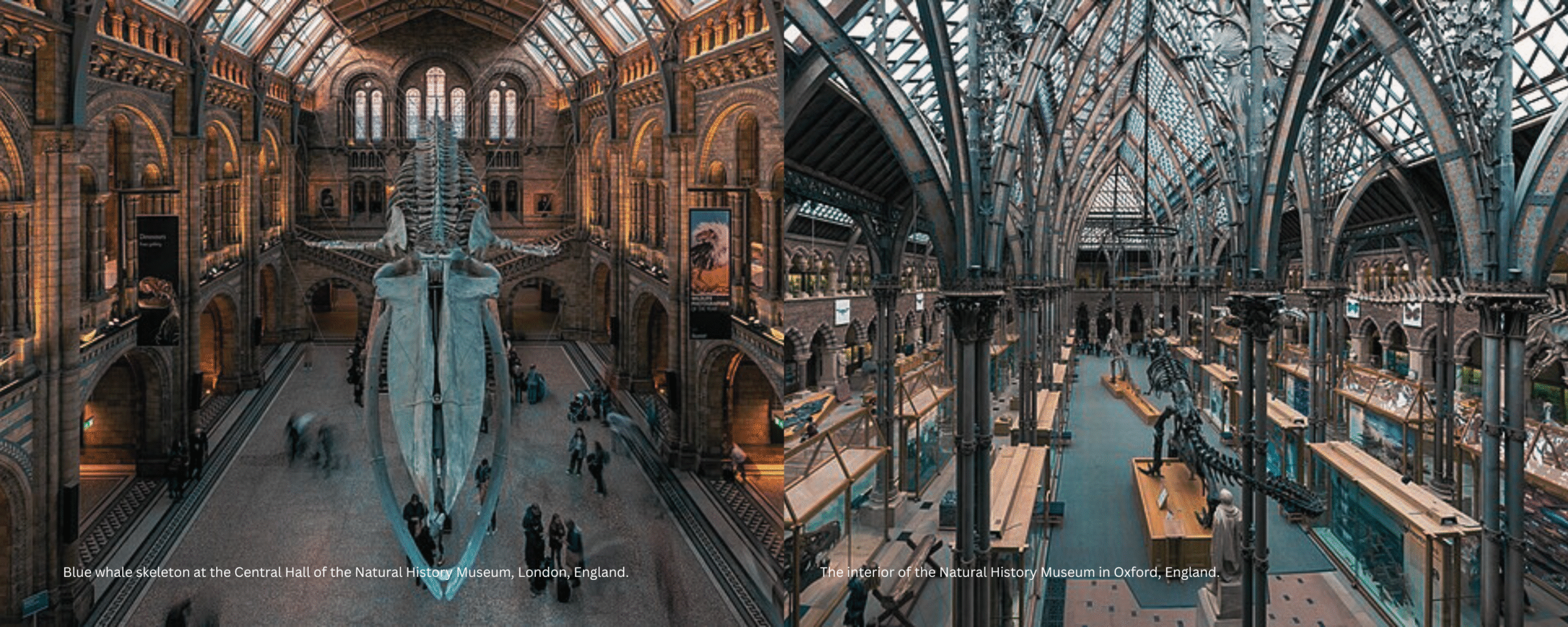

We would still create books, videos, and archives, but they would function more like artefacts than living knowledge. A library would be a cluster of symbols whose meaning nobody recalls how to decode. This parallels what anthropologists see in the loss of ancient scripts — such as Linear A from Minoan Crete — where the physical record remains, but the interpretive key is gone.

In such a society, every attempt at preserving history would become an act of futility. Teachers could lecture endlessly, but their students would wake up the next day as blank slates. Governments could pass laws, but enforcement would collapse when no one remembered the rules. Even personal identity would erode, since diaries and photographs would not be reminders but only mysterious relics of a self no one could truly recall. Human knowledge would shift from being cumulative to cyclical — endlessly recreated, rediscovered, and lost again, like waves erasing patterns in the sand.

The Political Consequences

Without personal or institutional memory, governance as we understand it would collapse. Laws require continuity of enforcement, treaties depend upon the preservation of trust across time, and effective leadership demands coherent policy direction. In a society where memory is universally impaired, the very foundations of political order would be destabilised.

Two broad outcomes can be theorised:

1. Totalitarian Stability Through Artificial Memory Systems

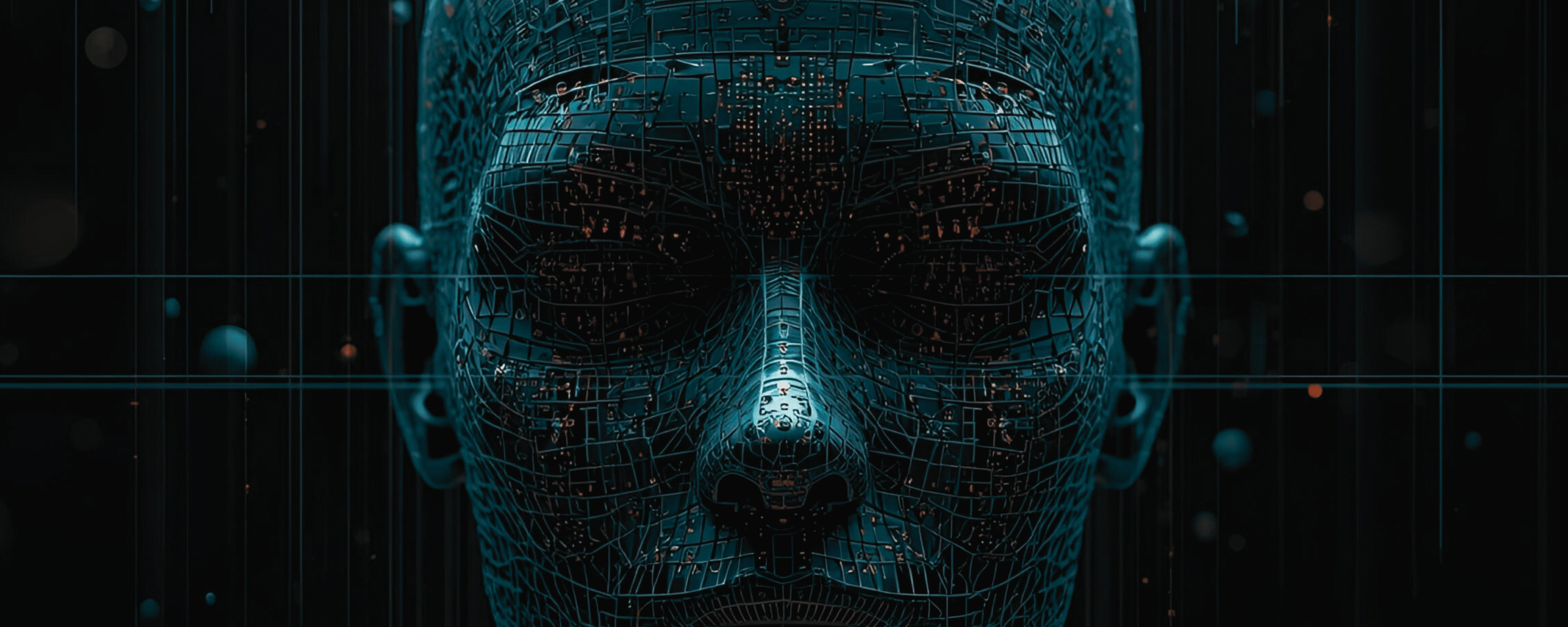

One possible trajectory would be the emergence of a highly centralised authority capable of storing, curating, and disseminating collective memory through artificial means. Digital archives or technological implants could become the substitute for organic memory, with citizens relying entirely on external systems to recall their history, laws, and identities.

The risks here are profound. Whoever controls the “memory infrastructure” would wield unprecedented power, not only shaping the narrative of the past but actively engineering the perception of the present. This parallels George Orwell’s concept of “memory holes” in 1984, where inconvenient facts are erased to maintain political dominance. Unlike Orwell’s fictional dystopia, however, a world without natural memory would leave no possibility of contradiction — reality itself would be whatever the authority prescribed. The result is a form of epistemological totalitarianism, where the boundary between governance and psychological control dissolves.

2. Perpetual Political Amnesia

A contrasting trajectory would be the absence of centralised memory systems, leading to fragmented and short-lived forms of governance. Political structures might devolve into micro-councils or neighbourhood assemblies, capable of making decisions only in the immediate present. Treaties, constitutions, and institutions would lack permanence; each day would begin with a clean slate, and each act of governance would be provisional.

This model resembles certain anthropological descriptions of stateless societies, where decision-making is situational and temporary, but scaled to the level of entire nations, it would produce chaos rather than harmony. Conflict resolution would be endlessly repetitive, with the same disputes resurfacing without historical context. Trust — the cornerstone of politics — could not exist when promises and agreements evaporate overnight.

This raises a deeper philosophical question: is political legitimacy rooted in the preservation of history, or in the ability to shape collective belief? In a world of universal amnesia, the answer might be both — and the tension between these poles could define the very possibility of governance.

The Collapse of Education

Learning depends on consolidation — the hippocampus encodes short-term information into long-term storage. Without it, the modern concept of education is impossible.

Children could be taught skills repeatedly, but retention beyond a few days would be negligible. Skilled labour, scientific research, and technological development would stagnate, if not regress entirely. The best we might achieve is a form of moment-to-moment skill coaching, where tasks are guided step-by-step in real time. Think of aviation, surgery, or engineering reduced to being conducted only under constant, direct instruction.

Social and Ethical Ramifications

Relationships lose continuity. Marriage, friendship, and family bonds rely on shared history. Social scientists note that trust is built through repeated positive interactions over time, which would be impossible without memory retention.

Crime and Justice collapse. Law enforcement depends on testimony, evidence recollection, and the deterrent effect of long-term consequences. In a universal Alzheimer’s world, the only effective justice system would be one of constant surveillance and immediate enforcement.

Moral Responsibility is questioned. If someone cannot remember committing a harmful act, can they truly be held accountable? Legal systems worldwide already debate this in cases of dementia-related crimes.

Technological Countermeasures

The most likely adaptation would be reliance on external, artificial memory systems — advanced AI or recording devices that provide constant, real-time identity and task reminders.

However, this introduces epistemic dependence: whoever designs and maintains the system controls what you “know.” This is not hypothetical — cognitive scientists like Andy Clark and David Chalmers have argued in their “extended mind” thesis that our smartphones already function as memory prosthetics. In a universal Alzheimer’s scenario, such prosthetics wouldn’t be optional — they would be our only link to a coherent self.

The Larger Philosophical Implication

Memory is not just a storage device; it is identity. Without it, the “self” becomes a momentary construct — a series of disconnected consciousness states. Derek Parfit’s work on personal identity suggests that in such a world, the continuity of personhood would vanish. Each day’s “you” would not meaningfully be the same as yesterday’s.

This transforms civilisation into a collection of individuals with no persistent selves, unable to engage in cumulative culture. Humanity’s survival would depend entirely on external systems — technological, political, or possibly religious — that impose continuity from outside.

Conclusion

A world where all humans have Alzheimer’s would not be one of chaos in the conventional sense — it would be one of stasis. Culture, science, and politics would freeze at the level of what can be acted upon in the immediate present. History would not simply be forgotten; it would cease to exist as a concept.

The ultimate power in such a world would belong to the custodians of artificial memory — and by extension, custodians of truth.

- Dr. Darshit Patel

- Blogs,Cryptic Aphorism

- 12 September 2025

- 13:00