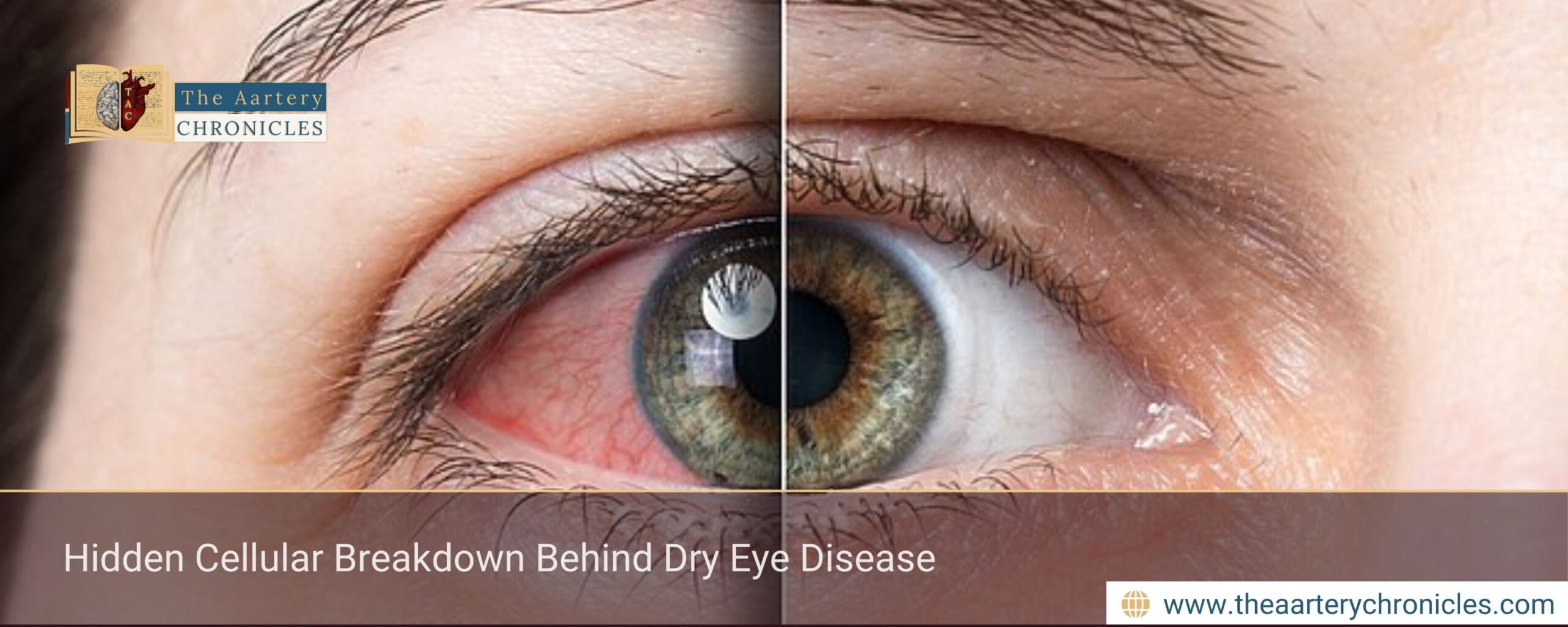

Hidden Cellular Breakdown Behind Dry Eye Disease

Summary: Dry eye disease affects millions worldwide, yet its root cause has remained unclear. Emerging research shows that a failure in autophagy, a vital cellular cleanup process inside tear glands, may be a key driver. Using lab-grown human tear gland organoids, scientists demonstrated how impaired autophagy disrupts tear production and damages gland cells, insights that may pave the way for novel, cell-targeted treatments.

A Hidden Cellular Breakdown May Be Driving Dry Eye Disease

What if dry eye disease starts not on the eye’s surface, but deep inside the tear glands themselves?

Recent stem cell–based research suggests that a subtle cellular malfunction may be at the heart of this common yet debilitating condition. This article explains how impaired cellular housekeeping inside tear glands contributes to dry eye disease, and what this discovery could mean for future therapies.

How Common is Dry eye Disease?

Dry eye disease (DED) affects an estimated 5–15% of the global population, making it one of the most prevalent ocular surface disorders. Patients often report persistent redness, burning, or stinging sensations, as well as eye fatigue that worsens during activities such as reading or prolonged screen use.

DED develops when the tear glands either fail to produce enough tears or generate tears with an imbalanced composition. Contributing factors include

- Allergies

- Autoimmune conditions

- Hormonal fluctuations

- Natural ageing process

If left untreated, dry eye disease can increase the risk of eye infections, cause microscopic damage to the corneal surface, and eventually impair vision.

Why Healthy Tear Glands are Important?

Tears are not just lubricants. They play a crucial role in:

- Flushing out debris

- Delivering oxygen and nutrients

- Defending against bacteria and other pathogens

For these functions to remain intact, tear gland cells must stay healthy, organised, and metabolically active. In dry eye disease, this internal balance appears to be disturbed, leading to reduced tear quantity and quality.

Autophagy: The Cell’s Internal Cleanup System

A growing body of evidence points to autophagy as a central player in tear gland health. Autophagy is a natural cellular recycling mechanism that removes damaged proteins and worn-out components, allowing cells to function efficiently over time.

In individuals with dry eye disease, autophagy within the tear glands appears to be compromised. When this cleanup system fails, cellular damage accumulates, weakening gland function and reducing tear output, key features seen in DED.

Growing Human Tear Glands in the Laboratory

To investigate this mechanism more closely, Sovan Sarkar and colleagues at the University of Birmingham (UK) developed human tear gland organoids from stem cells. Organoids are three-dimensional, lab-grown structures that closely replicate real human organs in both architecture and function. Their findings were published in Stem Cell Reports

These lab-grown tear glands contained all major cell types found in natural tear glands and were capable of producing essential tear proteins responsible for lubrication and antimicrobial defense. This made them an ideal model for studying both normal tear gland biology and disease states like dry eye disease.

What Happens When Autophagy Fails?

When researchers genetically disabled autophagy in the tear gland organoids, the consequences were striking:

- The normal cellular organization of the gland was disrupted

- Production and release of tear proteins dropped sharply

- Cell death increased significantly

These changes closely resemble the pathological features observed in dry eye disease, providing strong evidence that defective autophagy plays a central role in its development.

Potential for New Treatment Strategies

The research team also explored whether cellular damage could be mitigated. Treatment with nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) or melatonin improved cell survival and partially restored tear protein production in autophagy-deficient organoids.

These findings suggest that therapies aimed at improving cellular health and metabolic resilience, rather than only lubricating the eye surface, could represent a new direction in dry eye disease management.

Why This Discovery Is Important

“Autophagy is essential for proper tissue development and organ function. Here, we provide genetic evidence that autophagy is required for glandular tissue development by using autophagy-deficient human embryonic stem cells to generate tear glands with developmental and functional defects,” said Sovan Sarkar.

This human stem cell–based tear gland model offers researchers a powerful and accessible platform to study tear gland dysfunction in unprecedented detail. More importantly, it opens the door to testing targeted therapies that could restore tear production at its source.

Conclusion: What This Means for Dry Eye Disease

Dry eye disease may no longer be viewed solely as a surface-level problem. By uncovering a hidden cellular failure inside tear glands, this research reshapes our understanding of DED and highlights autophagy as a promising therapeutic target.

As science moves closer to treatments that protect and restore tear gland health, patients may one day benefit from longer-lasting, disease-modifying solutions rather than temporary symptom relief.

Dane

I am an MBBS graduate and a dedicated medical writer with a strong passion for deep research and psychology. I enjoy breaking down complex medical topics into engaging, easy-to-understand content, aiming to educate and inspire readers by exploring the fascinating connection between health, science, and the human mind.