From Small Pox to COVID 19: The Evolution of Vaccines Throughout History

Introduction

Vaccines, the unsung heroes of public health, have shaped the course of human history by safeguarding populations against infectious diseases. From the early days of variolation to the cutting-edge mRNA technology, the story of vaccines is a testament to human ingenuity and perseverance. Delve with us into this rich tapestry as we explore the fascinating history of vaccines.

Vaccine history isn’t confined to Jenner’s smallpox vaccine or the recent COVID-19 vaccines. It stretches back before the concept of vaccines, originating with methods like “inoculation” or “variolation.” This procedure, involving the use of smallpox lesion materials to induce immunity, has ancient roots in China, with the earliest written record dating back to 1549.

The Dawn of Variolation: From the 1400s to the 1700s

The practice of variolation, also known as inoculation, represents a significant chapter in the history of medicine. It involves deliberately infecting individuals with a mild form of a disease to induce immunity against more severe forms. Variolation was primarily used to combat smallpox, a highly contagious and deadly disease that ravaged populations for centuries.

The origins of variolation can be traced back to ancient civilizations in regions such as China and India. Historical records suggest that variolation was practiced in China as early as the 10th century. The method involved exposing individuals to smallpox scabs or fluid from smallpox lesions through inhalation or skin puncture. While the practice carried risks, including the possibility of developing severe smallpox, it was believed to confer immunity to the disease.

In 1721: Lady Mary Wortley Montagu introduced smallpox inoculation to Europe after witnessing the practice during her time in Turkey. She advocated for the inoculation of her own daughters, which helped to popularize the procedure in European society.

In 1774: Benjamin Jesty achieved a breakthrough by testing his theory that exposure to cowpox, a virus that affects cattle but can also infect humans, might provide immunity against smallpox.

Edward Jenner and the Small Pox Vaccine: During the late 1700s

The dawn of modern vaccination arrived with Edward Jenner’s groundbreaking work in the late 18th century. Jenner, an English physician, observed that milkmaids who contracted cowpox, a mild disease, seemed to be immune to smallpox. In 1796, he conducted an experiment where he inoculated a young boy with cowpox pus and later exposed him to smallpox, proving the protective effect of cowpox against smallpox. This seminal discovery led to the development of the smallpox vaccine, marking the birth of immunization as we know it.

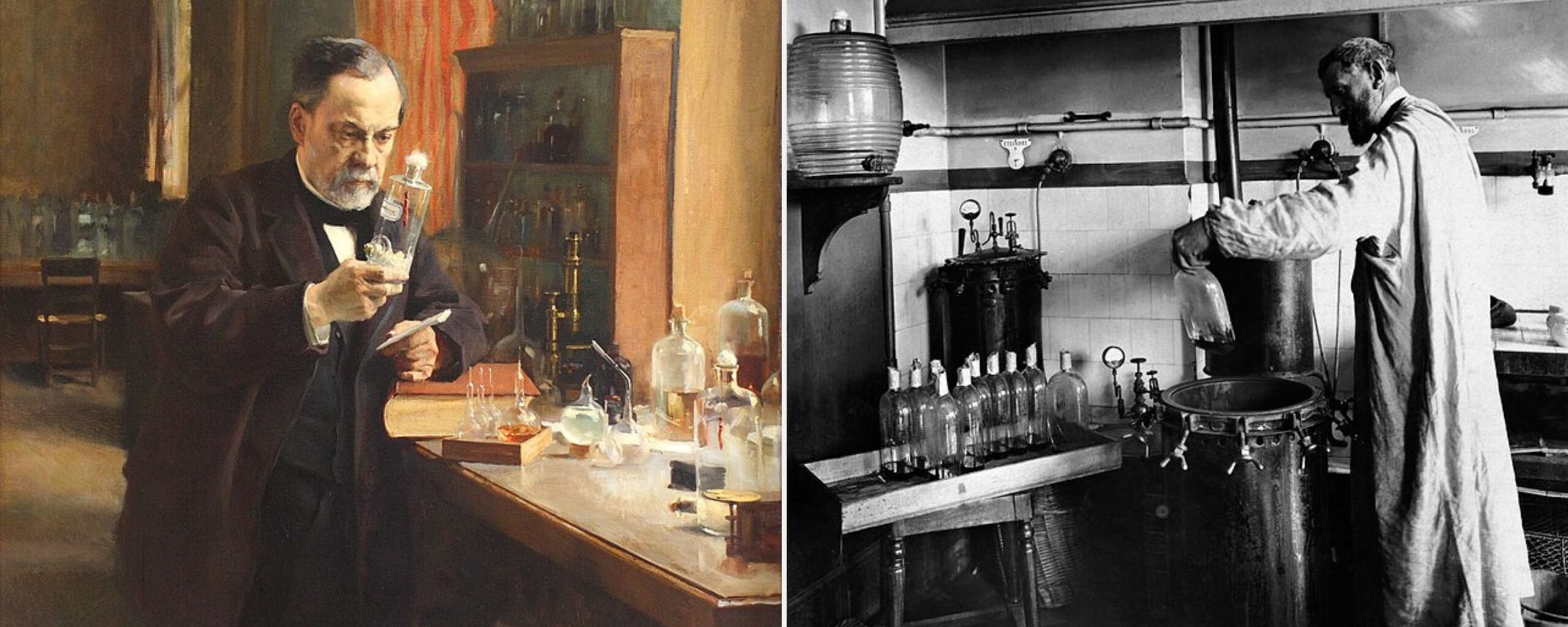

Attenuation: The Louis Pasteur Era of Vaccine in 1800

In 1872, Louis Pasteur overcame personal hardships, including a stroke and the loss of two daughters to typhoid, to pioneer the first laboratory-made vaccine: a solution for fowl cholera in chickens.

In 1885, Pasteur achieved a breakthrough in preventing rabies through post-exposure vaccination, despite facing skepticism due to his unsuccessful prior attempts with humans. Not a medical doctor himself, Pasteur embarked on a risky course of 13 injections with Joseph Meister, gradually increasing the doses of the rabies virus. Miraculously, Meister survived and later became the caretaker of Pasteur’s tomb in Paris.

A significant advancement in vaccination technology emerged with the use of a similar but less harmful form of the infectious agent. For example, cowpox was utilized as an analogue for smallpox. This approach involved weakening the pathogen, known as attenuation, before administering it as a vaccine. Other vaccines developed at or in association with the Pasteur Institute in Paris, France, followed this principle of pathogen attenuation before inoculation.

Toxoid Vaccine: During the late 1800s

In the late 19th century, scientists discovered antibodies, vital proteins that neutralize pathogens after infection. Recognizing the delay in their production post-infection, researchers sought safe ways to mass-produce antibodies. Administering these antibodies acted as an “immune patch” until individuals developed their own antibodies, marking the advent of the antitoxin era.

Anti-toxins, though not true vaccines, were produced by injecting toxins into large mammals like horses. These mammals generated antibodies against the toxin, which were then extracted, purified, and administered to individuals with the disease. However, in 1902, contamination of an anti-toxin with actual tetanus toxin resulted in injuries. This incident spurred the creation of the agency now known as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) by the US government, marking the initial move towards regulating medicines and therapies, a practice upheld to this day.

In the 1920s, scientists discovered that combining an antitoxin with a toxin could neutralize the toxin while still allowing the human immune system to respond to it. This led to the development of antitoxin-toxin vaccines for diseases like diphtheria and tetanus. However, many people experienced allergic reactions to the animal proteins used in antitoxin production. To address this issue, scientists devised a method to inactivate the toxin before administering it as a vaccine. This marked the beginning of toxoid vaccines, including those for diphtheria and tetanus, making protection against these diseases safer without relying on large mammals for production.

The 1900s Era of Vaccines

In 1937: The 17D vaccine against yellow fever was developed by Max Theiler, Hugh Smith, and Eugen Haagen. It received approval in 1938, and over a million people received it that year. Theiler was subsequently awarded the Nobel Prize for his contributions.

In 1939: The bacteriologists Pearl Kendrick and Grace Eldering demonstrated the efficacy of the pertussis (whooping cough) vaccine. Their research showed that vaccination reduced the rates at which children got sick from 15.1 per 100 children to 2.3 per 100.

Electron Microscopy

In the 1930s, the development of the electron microscope revolutionized virology by allowing scientists to visualize individual viral particles, classifying them based on shape and size without the need for cell culture or animal inoculation. This led to rapid advancements in viral research, including the identification and classification of viruses such as the influenza virus and the poliovirus. Vaccines against these viruses were quickly developed.

During the 1940s, scientists focused on developing vaccines against critical viruses like influenza, polio, and measles. They discovered that influenza and polio were not single viruses but consisted of multiple types, necessitating the development of different vaccines. This decade saw the rapid advancement of vaccine development against various viral diseases.

The Timeline of the Influenza Vaccine

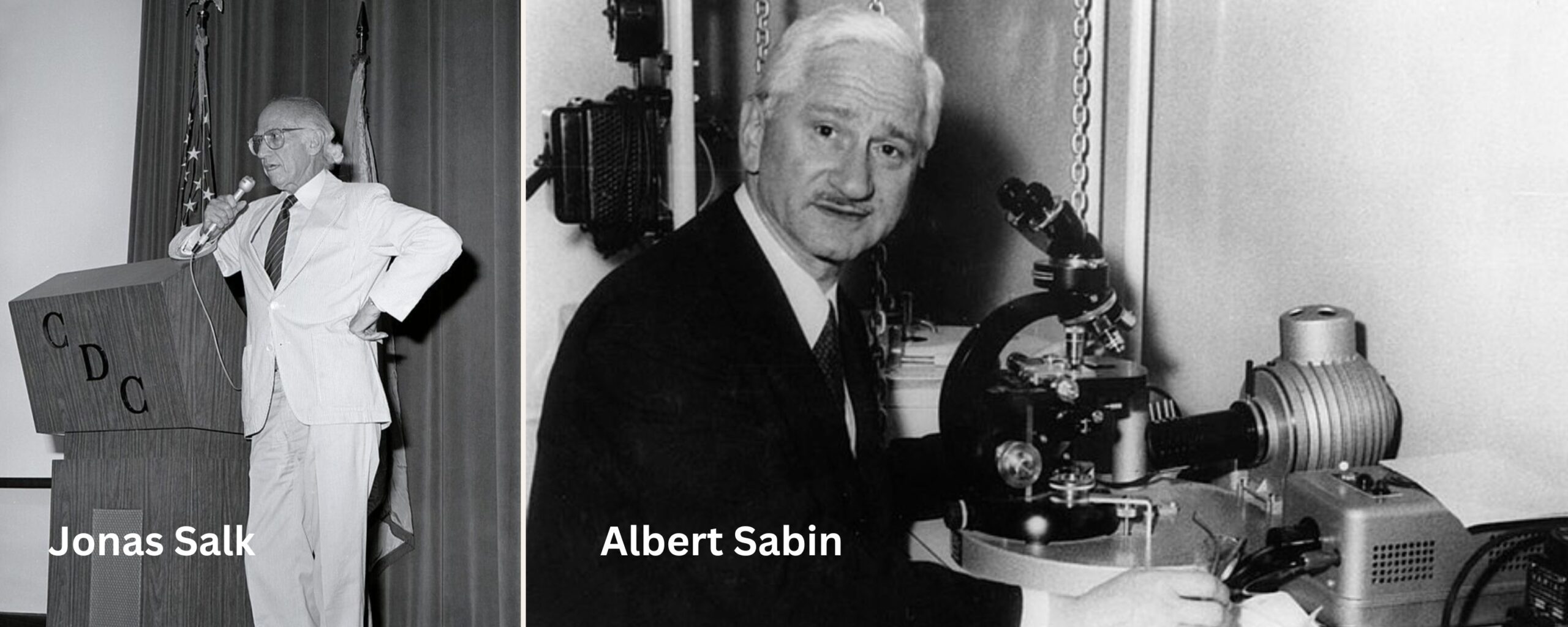

During the 1918-1919 Spanish Flu pandemic, which claimed an estimated 20–50 million lives worldwide, including many US soldiers, the development of an influenza vaccine became a top priority for the US military. Initial experiments with influenza vaccines, such as the testing of 2 million doses by the US Army Medical School in 1918, yielded inconclusive results. However, by 1945, the first influenza vaccine was approved for military use, followed by civilian approval in 1946. Doctors Thomas Francis Jr. and Jonas Salk led the research efforts, both later becoming closely associated with the polio vaccine.

The Discovery of Polio Vaccine

In the 1950s, Jonas Salk and his team defied established beliefs by developing the first killed virus vaccine for polio, challenging the notion that only live or attenuated viruses could induce an immune response. The groundbreaking work, which also involved contributions from Isabel Morgan, MD, and other women, saved thousands of children’s lives.

In the 1960s, following the Cutter Incident that shook public confidence in vaccines, Albert Sabin introduced the oral polio vaccine as a replacement for Salk’s vaccine. Tested successfully in the Soviet Union and Latin America, the oral vaccine was later introduced in the United States with significant success.

By the 1990s, polio had been eliminated from the United States and much of Europe, and by the early 2000s, it had been eradicated from the Americas, Europe, and most of Asia. However, localized outbreaks persisted in Africa and Central Asia. By the 2020s, types 2 and 3 of polio had been eradicated, leaving only type 1 in Central Asia.

Scientific Leaps and Advancements in the Era of Vaccines

In 1969: Dr. Baruch Blumberg, who had identified the hepatitis B virus in the preceding four years, collaborated with microbiologist Irving Millman to develop the inaugural hepatitis B vaccine. Their approach involved utilizing a heat-treated form of the virus in the vaccine’s formulation.

In 1971: Dr. Maurice Hilleman combined the measles vaccine, which had been developed in 1963, with recently created vaccines for mumps in 1967 and rubella in 1969 to form a single vaccination known as MMR.

In 1974: The World Health Organization (WHO) established the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI), now known as the Essential Programme on Immunization, with the aim of implementing immunization initiatives worldwide. The initial focus of the EPI included diphtheria, measles, polio, tetanus, tuberculosis, and whooping cough.

In 1978: A polysaccharide vaccine was licensed, offering protection against 14 various strains of pneumococcal pneumonia. By 1983, this vaccine was expanded to safeguard against 23 strains.

In 1985: the inaugural vaccine targeting illnesses induced by Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) received licensure, following the establishment of a company by David H. Smith for its production. Smith and Porter W. Anderson Jr. had collaborated on vaccine development since 1968.

In 1999: the initial vaccine targeting rotavirus, the leading cause of severe diarrhoea in young children, was withdrawn just one year after approval due to worries regarding the potential for intestinal issues. A safer version of the vaccine was introduced in 2006. However, it wasn’t until 2019 that this vaccine became widely adopted, being utilized in over 100 countries.

In 2006: the initial vaccine for human papillomavirus (HPV) received approval. The HPV vaccination proceeded to play a pivotal role in the endeavour to eradicate cervical cancer.

In 2019: The pilot implementation of the malaria vaccine was launched in Ghana, Malawi, and Kenya. The RTS/S vaccine became the first vaccine capable of significantly reducing the deadliest and most prevalent strain of malaria in young children, who are at the highest risk of succumbing to the disease.

In 2021: The World Health Organization (WHO) prequalified an Ebola vaccine for use in countries at high risk as part of a broader array of tools in response to the disease. In 2021, a global vaccine stockpile was established to ensure a swift response to outbreaks. Moreover, a third-generation smallpox vaccine received approval for preventing monkeypox, marking a significant milestone as the inaugural vaccine for this disease

COVID-19 Outbreak and Vaccine Development

On January 30, 2020, the Director-General of the WHO declared the outbreak of the novel coronavirus 2019 (SARS-CoV-2) to be a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. By March 11, the WHO had confirmed COVID-19 as a pandemic. Effective COVID-19 vaccines were swiftly developed, manufactured, and distributed, with some utilizing innovative mRNA technology. By December 2020, just one year after the first COVID-19 case was detected, the first doses of COVID-19 vaccines were administered.

Throughout 2021, the roll-out of COVID-19 vaccines continued, with doses delivered and administered across continents. However, efforts to combat the pandemic were hindered by disparities in vaccination coverage. As of July 2021, nearly 85% of vaccines had been administered in high- and upper-middle-income countries, with over 75% distributed in just 10 countries.

Conclusion

For more than 200 years, vaccination has been crucial in preventing deadly diseases since the development of the first smallpox vaccine. History emphasizes that effectively addressing vaccine-preventable diseases globally necessitates time, resources, collaboration, and ongoing vigilance. From early techniques in the 1500s to modern innovations like COVID-19 vaccines, significant progress has been made. Vaccines now provide protection against over 20 diseases, such as pneumonia, cervical cancer, and ebola. Over the past three decades alone, child mortality has decreased by over 50%, largely due to vaccines. However, continued efforts are vital for further advancements in global health.

- Dr Anjali Singh

- Infectious Diseases,Pharmacology,Public Health

- 22 April 2024

- 11:00

Reviewed by Dr Aarti Nehra (MBBS, MMST)