Enhancing Memory: Protect Your Brain’s Best Asset

Introduction

Memory is an incredible ability that helps shape our identities and navigate daily life. It enables us to hold on to cherished moments, recall critical information, and learn from past experiences. However, memory isn’t flawless—it can sometimes fail, leading to forgetfulness or misremembered details.

By understanding how memory works, from how it’s formed to why it sometimes falters, we can uncover ways to improve it and protect it as we age. This article delves into the fascinating process of memory, the different types it encompasses, and practical tips to strengthen it. Memory is not just about holding onto the past—it’s also a powerful tool for building the future.

Types of Memory

Memory is how our brain stores and retrieves information when we need it. There are four main types of memory, each with a specific role:

1. Sensory Memory

Sensory memory is like a quick snapshot of what we see, hear, or feel. It lasts only for a moment, just enough to recognize something before it fades

For example:

Iconic Memory: What you see, like a brief glance at a picture.

Echoic memory: What you hear, like a sound that lingers for a few seconds.

Haptic Memory: What you feel, like the touch of someone’s hand.

2. Short-Term Memory

Short-term memory is like a temporary storage space in your brain. It holds information for a short time (about 15–30 seconds) so you can use it right away. For example, remembering a phone number long enough to dial it. You can keep this information longer by repeating it.

3. Working Memory

Working memory is like a mental notepad. It helps you use and manage small bits of information while performing a task, like solving a math problem or following a recipe. Some consider it a part of short-term memory, but it’s more active.

4. Long-Term Memory

Long-term memory stores everything you want to remember for a long time, from childhood events to skills like riding a bike. It has no limit on how much it can hold.

There are two types of long-term memory:

Explicit Memory (Conscious): Memories you actively recall, like birthdays or facts. These can be:

Episodic memory: Personal events, like your first day at school.

Semantic Memory: Facts and knowledge, like the capital of India.

Implicit Memory (Unconscious): Skills or habits you learn without thinking, like riding a bike or typing.

How Memory Works

Memories go through three stages:

Encoding: Taking in information through your senses.

Storage: Keeping the information in your brain.

Recall: Retrieving it when you need it.

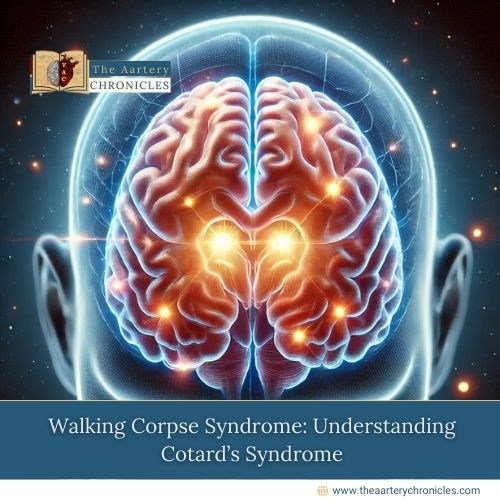

Parts of the Brain Involved in Memory

Memory is a complex process involving several parts of the brain. Researchers have long debated whether memories are stored in a single area or distributed across different brain regions. Early research by Karl Lashley explored the idea of an engram—a physical representation of memory—by creating lesions in animals’ brains. Despite his efforts, Lashley found no evidence of a localized memory trace. Instead, he proposed the ‘equipotentiality hypothesis’, which suggests that if one part of a memory-processing area is damaged, another part can compensate. Today, scientists know that specific brain regions are key to different memory processes.

Amygdala

The amygdala plays a central role in regulating emotions such as fear and aggression. It helps encode memories more deeply when they are emotionally charged, influenced by stress hormones. For example, fear-conditioning studies in rats have shown that when neurons in the lateral amygdala are damaged, fear memories can fade. The amygdala also aids in memory consolidation, helping to transfer new learning into long-term storage.

Hippocampus

The hippocampus is crucial for processing declarative and episodic memories as well as recognition and spatial memory. Studies involving hippocampal lesions in rats have shown impairments in maze navigation and object recognition tasks. Additionally, the hippocampus connects new memories to existing ones, providing meaning and context. Damage to this area, such as in the famous case of patient H.M., can prevent the formation of new declarative memories, while older memories remain intact.

Cerebellum

While the hippocampus is essential for explicit memories, the cerebellum supports implicit memories, such as motor learning and procedural tasks. Research on classical conditioning, like the eye-blink response, has demonstrated that damage to the cerebellum prevents subjects from learning these automatic responses, emphasizing its role in procedural memory.

Prefrontal Cortex

The prefrontal cortex is associated with higher-order cognitive processes like semantic memory and decision-making. Brain imaging studies have shown that different regions of the prefrontal cortex activate during tasks involving memory encoding and retrieval. For example, semantic tasks activate the left prefrontal cortex, while perceptual tasks show less engagement.

Neurotransmitters and Memory

Memory formation also relies on neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin, glutamate, and acetylcholine. These chemicals facilitate communication between neurons, strengthening synaptic connections through repeated activity. Emotional arousal can boost the release of neurotransmitters like glutamate, enhancing memory formation, as suggested by the ‘arousal theory’. Strong emotional events often result in vivid recollections, known as ‘flashbulb memories’, although their accuracy can diminish over time.

Here’s a simplified explanation based on the provided content

How Our Brain Forms and Stores Memories

Memory is our brain’s way of storing information so we can recall it later. It helps us survive, guides our decisions, and shapes our identity. Memories can be short-term, lasting a few seconds, or long-term, lasting for years or even a lifetime.

How Memories Are Made

When a memory is first formed, it is fragile and can be easily disrupted. Over time, through a process called ‘memory consolidation’ it becomes stronger and stable. If a memory is later recalled, it can temporarily become fragile again, but through ‘reconsolidation’, it can be strengthened or even modified.

Biological Processes Behind Memory

When we learn something, it triggers changes in the brain at the molecular level. Specific proteins and genes, like CREB, are activated to strengthen the connections between brain cells. These changes help store the memory for the long term.

Role of Stress in Memory

Stress can have both positive and negative effects on memory:

Positive Stress: Moderate levels of stress help us remember important events better.

Excessive Stress: Too much or chronic stress can harm memory. Stress hormones, like cortisol, affect brain pathways and may weaken memory over time.

Clinical Applications

Understanding these processes has important implications. Scientists are exploring ways to strengthen weak memories or reduce harmful memories, like those linked to PTSD or anxiety. For example, medications or therapies could target the stress-related pathways in the brain to improve memory or emotional well-being.

Some ways to improve memory

1. Focus on one thing a a time

Avoid multitasking. Giving your full attention to a task helps your brain process and store information more effectively.

2. Get Organized

Keep a planner, write to-do lists, or use phone reminders. When your tasks are organized, your brain has more space to focus on remembering important details.

3. Repeat and Recall

When you learn something new, repeat it several times. Try recalling the information later in the day or teaching it to someone else to strengthen your memory.

4. Create Associations

Link new information to something familiar. For example, to remember a name, associate it with a person or object you already know.

5. Visualize Ideas

Turn ideas into mental images. For instance, if you want to remember a shopping list, picture the items vividly in your mind.

6. Take Breaks

Short breaks between activities can give your brain time to absorb and process information. Overloading yourself can make it harder to remember things.

7. Stay Physically Active

Exercise boosts blood flow to the brain, improving memory and overall brain health. Even a brisk 20-minute walk can help.

8. Sleep Well

Good sleep is essential for memory. Aim for 7–9 hours of quality sleep to give your brain time to rest and consolidate information.

9. Eat Brain-Friendly Foods

Incorporate foods like nuts, berries, fish, and leafy greens into your diet. These provide nutrients that support brain health.

10. Practice Mindfulness

Meditation and mindfulness exercises reduce stress and improve focus, making it easier to remember things.

11. Use Mnemonics

Turn information into rhymes, acronyms, or short phrases. These memory aids make recalling details fun and easy.

12.Engage Your Senses

Using multiple senses can strengthen memory. For example, read information aloud or associate a smell with a memory.

13.Stay Curious

Challenge your brain by learning new skills, playing puzzles, or reading about different topics. Keeping your mind active strengthens your memory over time.

14. Manage Stress

Stress affects memory negatively. Practice relaxation techniques like deep breathing, yoga, or spending time in nature to stay calm.

15. Stay Social

Interacting with others stimulates your brain and improves memory. Spend time with friends, family, or join groups to stay mentally sharp.

Factors Influencing Our Memory

- Emotion and Attention: Emotional experiences leave a stronger mark on memory. Fear, happiness, or sadness can make events more memorable. The amygdala, a part of the brain, plays a big role in this by focusing our attention on emotional details.

- State of Mind: How we feel while experiencing something affects how we remember it. We recall sad events better when we’re sad, and happy ones when we’re happy.

- Environmental Impact: Distractions around us can interfere with how memories form. A quiet and focused environment helps in better memory retention.

- Physical Brain Health: Parts of the brain like the hippocampus and temporal lobes are vital for forming and storing memories. Damage or illness in these areas can weaken memory.

- Emotional Content: Events with emotional intensity, like joy or fear, tend to stick with us more than neutral experiences. Women, in particular, often remember emotional events better than men.

- Suggestions and Preconceptions: Memories can be influenced or even altered by suggestions or biases. For example, being told something happened might lead us to “remember” it, even if it didn’t.

- Experience and Connections: Each experience changes the brain’s neural connections. These connections can strengthen or weaken over time, depending on how often the memory is recalled or the neurons are repurposed.

- Fear and Stress: Repeated fear-inducing situations can make memories of those fears more intense and easier to trigger, creating a cycle of anxiety.

- Reconsolidation of Memories: Every time we recall a memory, it might be reshaped slightly based on new experiences or interference, showing how dynamic memory is.

Conclusion

Memory is a remarkable capability that supports every aspect of life, from learning and decision-making to emotional connections. While it is prone to lapses, understanding its processes and adopting memory-boosting habits can significantly enhance its performance. By nurturing our memory, we not only preserve our past but also lay a strong foundation for a better future.